Witchcraft

Belief

in the power of witches, and the persecution of witches by church authorities,

was widespread throughout

Witches

were thought to be in league with the Devil, who was their master. The Devil,

or Satan as he is sometimes called, is believed to roam the world looking for

human souls to tempt into Hell. He is the supreme spirit of evil, the enemy of

all that is good and holy. According to Christian tradition the Devil is a

fallen angel, Lucifer, who was driven out of heaven. The Devil has supernatural

powers which he uses to ensnare the souls of men. The Devil has many names and

appears in many forms. He has an army of minor devils, demons and hobgoblins to

help him. His evil task is to drag as many human souls as possible down into

Hell. The Puritans believed in, and feared, the Devil and all his works, as did

many Christians at the time. Some people still believe that there exists a

power of positive evil, and that the Devil is a personification of this evil.

Witches

were believed to have certain powers given to them by their master, the Devil.

It was believed that they could make themselves invisible, or change themselves

and others into animals, birds or other creatures, and that they could fly.

They could, supposedly, create charms and cast spells; cause sickness and death

to people or animals simply by looking at them (giving them the evil-eye), or

by sticking pins or needles into an image of the victim. It is easy to see how,

in a society with few scientific answers to the problems of sickness and death, these might be attributed to malicious supernatural

agencies.

The

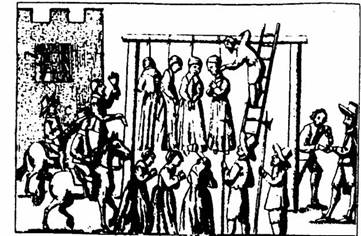

Christian churches pursued and persecuted supposed witches. A common test for a

person accused of being a witch was pricking with a needle. All witches were

supposed to have somewhere on their bodies a mark, made by the Devil, that was

insensitive to pain. If such a mark was found it was regarded as proof of

witchcraft. Other marks also were looked for as proof, things like warts, extra

nipples, extra fingers or toes which were supposedly used to suckle familiars -

creatures of the Devil who helped the witch. Other proofs of witchcraft were

the inability to weep, and the ability to float on water. The water test

involved throwing the accused into a river or pond. If they sank (and possibly

drowned) they were innocent; if they stayed afloat they were guilty. The tests

for witchcraft were cruel, and so were the punishments if found guilty. Witches

were often hung or burnt at the stake.

The

witchcraft trials in

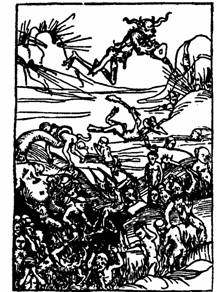

This

engraving showing the demonic hordes of Hell catching the souls of sinners, is attributed to Albrecht Durer. From Warning vor der falschen

lieb dieser werit, printed by Peter Wagner,